THE AUSTRALIAN: Adrift in a sea of apathy

Rohingya refugees from Myanmar sit in a police truck in East Aceh after they were rescued this week off the coast of Indonesia. Source: AFP

They are the world’s most persecuted people, their plight recognised as such by the UN and sometimes compared to that of Europe’s Jews in the 1930s.

Yet as the full horror endured by the hundreds of hapless Rohingya boatpeople who have now been allowed to land in Indonesia and Malaysia emerges, prospects of alleviating the appalling conditions in Myanmar that led to their desperate escape from the hell of their homeland appear remote.

For, while the world has been transfixed by graphic news coverage of their plight at sea, within Myanmar there has been virtually no mention of it in the largely government-controlled media.

And the reason for that lies at the heart of the grim humanitarian crisis that is confronting our region and that has the potential to spark a new flood of refugees seeking asylum: there are an estimated 1.1 million Rohingya people in Myanmar. They trace their antecedents back to Burma in the 19th century under British rule. But these days they are “non-people” in the land of their birth: stateless, without legal or civic rights, subject to wanton discrimination and denied education, healthcare and the right to work.

They are a Muslim ethnic minority centred on the western state of Rakhine. They have been there for generations. Yet when the former generals who run Myanmar’s now purportedly democratic government announced the results of a referendum last year, there was no mention of the Rohingyas among the country’s 135 officially recognised ethnic groups.

Incredibly, they were told they were Bengalis — as the Buddhist majority calls them — from across the border in Bangladesh who were in Myanmar illegally and therefore subject to deportation. This categorisation has given fresh impetus to the protracted ethnic violence to which they have been subjected.

Yet Bangladesh does not recognise them as Bengalis. And after what has been described as “two bouts of vicious ethnic cleansing by Rakhine (Buddhist) nationalists”, particularly around the state capital of Sittwe, more than 150,000 of the 1.1 million Rohingyas have been confined to camps ringed with barbed wire where, aid groups say, they are denied even humanitarian help.

Grimly, a recent report issued by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, following a visit by officials to Myanmar in March, speaks of the “early warning signs of genocide in Burma”, noting, according to The Washington Post, that the Rohingyas are subject to dehumanising hate speech, physical violence, segregation, dire living conditions, restrictions on movement, land confiscation, sexual violence, arbitrary detention and other human rights violations.

Against the backdrop of ethnic violence that has killed scores of Rohingyas, the report warns of the “grave risk of additional mass atrocities and even genocide”.

The animosity of the overwhelming Buddhist majority towards the Muslim minority underpins the crisis. Between 80 per cent and 90 per cent of Myanmar is Buddhist and deeply suspicious of Muslims, even though the country neighbours Muslim Bangladesh and the Rohingyas in Myanmar follow a mild form of Sunni Islam that has shown no previous tendency towards extremism or militancy. Buddhist monks are blamed for inciting “Islamic invasion” fears in relation to the Rohingyas, who have been referred to as “dark-skinned” interlopers who have no place in the country.

Successive Buddhist rampages against the Rohingyas have led more than 100,000 to flee by boat, falling prey to wily people-smugglers who have taken them mainly to Malaysia and Thailand. Thousands more are reported to have fled overland. The Myanmar authorities are clearly more than happy to see them go. They have done nothing to impede their exit.

Hopes Myanmar’s recent moves towards democratisation would improve the lot of the Rohingyas have not been realised. Instead, their situation has deteriorated. The lifting of restrictions on the media has led to more vitriolic attacks against the Muslim minority, while Buddhist extremists have been further emboldened to stir up popular sentiment against them.

A general election due in November also has exacerbated their plight, with anti-Rohingya and anti-Muslim sentiment an issue on which the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party of President Thein Sein appears confident of being able to win badly needed votes.

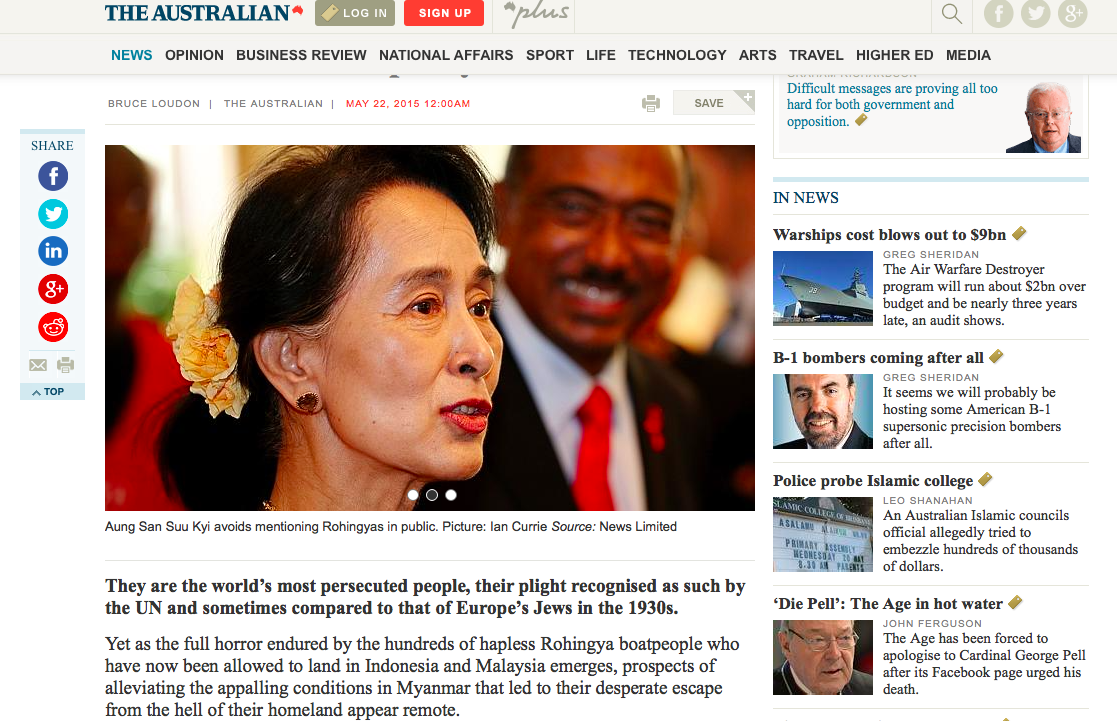

Surprisingly, the country’s globally admired opposition leader, Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, herself the victim of prolonged repression at the hands of military rulers, has failed to take up cudgels on behalf of the Rohingyas. Previously a doughty campaigner on human rights issues, Suu Kyi largely has been silent on their plight, apparently more concerned not to risk a Buddhist backlash against her National League for Democracy, which she hopes will emerge victorious in November — although she is barred from running as a candidate for the presidency.

So cautious is Suu Kyi on the issue that at press conferences she tries to avoid even using the word Rohingya. However, a political analyst with access to Suu Kyi quotes her as saying: “I am not silent because of political calculation. I am silent because whoever’s side I stand on, there will be more blood. If I speak up for human rights, they (the Rohingyas) will suffer. There will be more blood.”

Suu Kyi’s silence has been widely condemned, with Britain’s The Times describing her unwillingness to take a stand on the plight of the Rohingyas as “shabby” and noting that “she has a moral duty to help those who are disenfranchised, as she once was”.

Electoral imperatives vested in the anti-Rohingya attitude of the Buddhist majority are, however, a paramount consideration for Suu Kyi and Thein Sein, and doubtless this has accelerated the pace of Rohingyas seeking to flee Myanmar ahead of the imminent monsoon in the Bay of Bengal, when travel on small boats becomes even more perilous.

There is no certainty about how many have left in recent weeks and months. UN officials know of at least 6000 who have been in exceedingly dire straits aboard boats heading for Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand. But the actual numbers, according to aid agencies, are likely to be much higher, with no credible estimate of how many may have died at sea.

Another dimension to the crisis has been provided by human rights groups in Thailand, where authorities have uncovered mass graves of Rohingya boatpeople apparently brought to remote parts of the country from Myanmar by people-smugglers.

In one grave in Thailand’s Songkhla province there were 26 corpses, and human rights group Fortify Rights has said it believes many more Rohingyas have been killed as they have attempted to find new lives away from the purgatory of their existence in the country of their birth. Rohingya survivors in Thailand have spoken of regular killings of boatpeople, with traffickers trying to extort more money from their victims.

Interviews carried out by Fortify Rights have highlighted the misery of boatpeople in camps they are taken to, with one survivor reporting hundreds of deaths during the two months she was at a camp in a mountainous area near the Thai border with Malaysia.

Thailand, though it is the most sought-after destination for the hapless Rohingyas, has a poor record on people-smugglers.

Last year the US State Department found Thailand was not meeting the minimum standards required of countries to combat human trafficking. Yet progress in tackling the Rohingya crisis depends to a considerable extent on an emergency meeting due to take place in Bangkok next week, which will bring together governments from across the region, including Australia, to discuss the issue.

The backdrop to the meeting could hardly be more portentous for countries such as Australiathat invariably top the list as the preferred destination for refugees in our region.

So far this year, according to UN estimates, at least 25,000 Rohingyas have fled Myanmar to seek new lives elsewhere.

But given conditions in which the 1.1 million Rohingyas in Rakhine state and across the border in Bangladesh are compelled to exist, there seems little doubt the number joining the exodus and signing up with people-smugglers could rapidly escalate.

Some aid workers talk of a “terrifying” humanitarian crisis that could see many tens of thousands of Rohingyas fleeing and seeking new homes in our region.

Yet the Myanmar government, which holds the key to solving the crisis, is not even willing to attend the talks in Thailand, apparently unconcerned about the exodus of Rohingyas and unwilling to do anything to make their lives more bearable and encourage them to stay in Myanmar.

Myanmar seems certain to come under intense pressure at the Thailand meeting to take measures that will ease the appalling plight of the Rohingya and give them cause to stay in the country rather than flee.

But with the November election looming, it will be surprising if the hardline government in Naypyidaw bows to pressure that would likely further inflame passions among the Buddhist majority. There is, however, scope for such pressure.

The international community has done a great deal to facilitate Myanmar’s transition from an internationally reviled military dictatorship targeted with sanctions to a country that is on a trajectory towards becoming a parliamentary democracy.

Australia has played a particularly important role in encouraging democracy in Myanmar, and in 2015-16 will give the country more than $60 million in aid. That has been supplemented by Foreign Minister Julie Bishop’s announcement of an extra $6m related specifically to the refugee crisis. US President Barack Obama, too, has been at the forefront of rewarding Myanmar for its progress towards democratic change, paying a visit to the country that set the seal on its emergence from years of diplomatic isolation and sanctions.

Despite this, the authorities in Myanmar appear unmoved and, without a domestic constituency pressing them to improve the lot of the Rohingyas, it seems unlikely they will do anything to help.

“They (the Myanmar authorities) have no interest in the Rohingyas. They are happy to see them go and they are unlikely to change their stance unless serious international pressure is brought to bear on them over the issue,” a diplomat familiar with the crisis said last night.

He added: “But until the election is over and done with, I’d be surprised if anything happened.”

The arrival of the monsoon is likely to stop the boats in the short term. But the outlook beyond that is daunting, with appalling conditions of wanton discrimination and deprivation imposed on the Rohingyas by a government determined to do the bidding of the extremist Buddhist majority.

There are fears, indeed, that the election itself could become a spark for further violence against the Rohingya minority, sending more boatpeople into the arms of the same unscrupulous people-smugglers responsible for the horrifying plight of the refugees who have now arrived in Malaysia and Indonesia.

Getting the authorities in Myanmar to change course and stop the persecution that has turned the Rohingyas into stateless “non-people” won’t be easy.

But it is something that must be achieved if humanity is to prevail in Myanmar and the tide of asylum-seekers halted.

Reprinted from THE AUSTRALIAN